Remember When

Duncan Clarke

Contents

- Hondo

- Memory Lane

- Ghosts

- Memoire

- Exodus

- Rhodies Till We Die

- Politics

- Nightfall

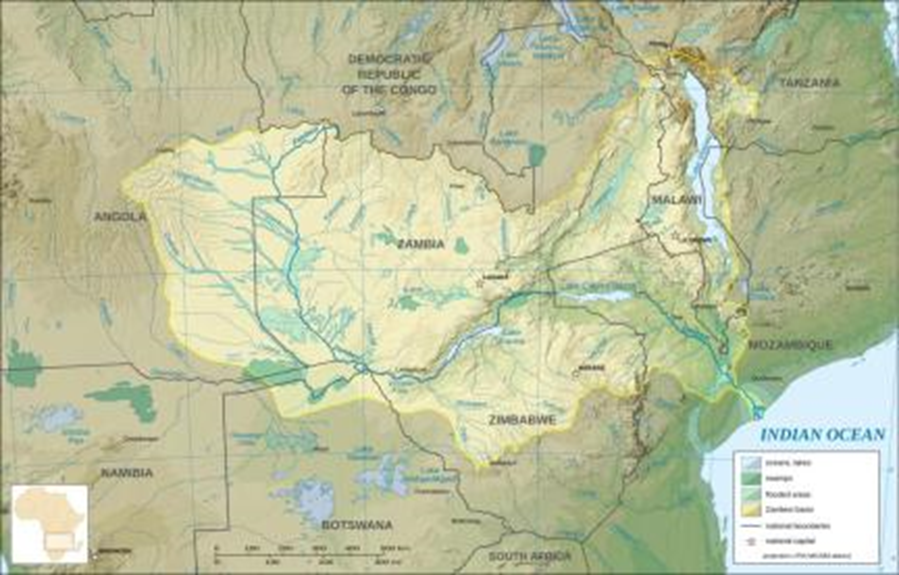

- The River

About the Author

The heat coming off the Zambezi and in the valley that October evening was the sort that clung to the skin like a damp shirt. It was the suicide month after all.

The river shimmered bronze beneath the late sunset horizon, hippos concealed somewhere in the water reeds.

The cicadas screamed out as if to prove they could out-shout Mosi-oa-Tunya’s distant thunder.

A small sign, half-painted, hung over the veranda of the Zambezi Drift River Bar:

Cold Beer, Hot Stories, No Credit – Ever.

Typical Rhodie hang-out, hanging on for survival, as was everyone else still living in the environs, following a decade-plus of bush war and nearly fifty years of chaos and mayhem under Mugabe and his slick sidekick, Mnangagwa.

At one of the wrought iron-outside tables sat an old top, a regular, Pete “Bokke” Wainwright, glass of Lion beer sweating in his mangled hand, the rim ringed with salt and dust.

He’d been there since half-past four, long enough for the barman – an old chap called Banda – family originally from Nyasaland, back in the old days – who had known and remembered the war only as a boy, and with skill, guessed that Bokke would finish his first dop before the sun hit the mopane trees.

Hondo

Across the table, after arriving late as usual, came Chris “Chooks” Vaughan – much lighter build, neater shirt, that St George’s College boarding regime and regimentation had instilled, including unchanged neatness still somewhere in his posture.

Yet, the years had bent him a little.

Cooks dropped into the wicker chair with a sigh, removed his battered bush hat, and said, “Yussus, boet, it’s ballie hot. Thought the devil was braaiing the rocks on the road in from that new Chinese airport.”

Bokke grinned without humour. “October, chief. Suicide time again. You’d think the old terrs lit the place up again.”

“Ag shame, man, don’t start with hondos already,” Chooks laughed. “We’ve just got into our first chibulie and you’re already marching the sticks into contact.”

Banda slid a second beer onto the table, Zambezi this time. The foam rolled lazily over the glass lip; cold enough that Chooks groaned in appreciation. “Lekker mushi, hey, Tatenda.”

They drank their beers in silence for a moment, both letting the heat and memory settle.

“You still driving that clapped out Landy?” Chooks asked.

“Landy? Pegged off long ago, boet. Gearbox frot, same as my back. Sold it to some oke from Harare North – said he’d restore it. Probably flogged it for parts.”

Chooks chuckled. “That Landy saw more action than most museums. Remember you used to stick the RLI crest and Sable horns on the bonnet?”

“Ja. Bit of bulldust pride, hey. Those were days when we still thought the bloody place would hold.”

He took another swig; eyes fixed on the river. “Now look at it. Farms gone, towns half empty, everyone with a brother, sister cousin, uncle or tannie in Jozi, or Perth. Even the Mozzies have emigrated.”

“Don’t be domkop,” Chooks said. “It’s still home.”

Bokke gave a dry snort. “Home? My old plaas near Mount Darwin got grabbed twenty years back. Gooks came with papers, then without. By the third time they didn’t need papers. Wovets had badzas, knives and guns.

I packed the bakkie and gapped it to Vic Falls. What’s left of home’s sitting right here in this bar, ek se.”

Banda brought another round without being asked. The sun slanted down, painting both men in the sundown light of gold.

Memory Lane

“You remember that night in Umtali,” Chooks said, “when the power went out and we nicked those candles from the Marymount Convent? Whole dorm was smelling of tallow and guilt.”

“Ja, and that prefect caught us. Told him the terrs had cut the power.” Bokke laughed then, genuinely. “He believed us. Gave us detention instead of canning. Called it, DB, like the army. Everything was DB in those days, hey.”

They traded school faded memories — sadza with relish in tin bowls, Zambezi mud for porridge, the smell of Fray Bentos stew from home, packages of bikkies, the thrill of getting a letter from a girl in Bamba Zonke or Skies.

The slang came naturally, sliding back into place like an old rifle bolt.

“You were the Umtali boy. Proper bundu bloke,” Chooks said. “I was just a townie. Saints taught us how to pray, tie a tie, not how to fix a borehole.”

“Ja, but you learned how to sneak wine from the sacristy.” White and red dop, all in one go. “Payment in kind for zot work, hey”.

“Bin 16,” Chooks laughed. “Or Dustbin 16, the communion vintage of Jesuit fwaps, cattle-ticks, and piss cat champions”.

They laughed long and loud, startling a flat dog and heron from the bank.

By sunset the bar filled with a few tourists – a few Germans smelling of sunblock, a pair of South Africans from Down South arguing about load-shedding back home.

The Boeties had no idea of the darker future that awaited them, thought Bokke.

Banda switched on the lanterns and the first bats flitted through the glow.

Ghosts

Chooks watched the tourists, and said quietly, “Funny, hey. They see only the Falls. Not the ghosts.”

“Ghosts are better company than some of the living,” Bokke said. “At least they don’t ask for forex.”

He leaned back, gaze turned inward. “You ever think how we got from stick patrols in the bush to this? Two old Rhodies drinking cheap beer, waiting for the power to be cut again.”

Chooks smiled gently. “Could be worse, boet. Could be Down South paying for water, crime insurance and load-shedding electricity.”

“Ha! At least Down South the shop tills still work, and there’s petrol, for now.” The night slid in and passed by with the slow patience of the Zambezi current.

Lantern light pooled gold on to the table; somewhere in the reeds, frogs began their steady chorus.

The first whiskey bottle had replaced the beers; the ice melting faster than Banda could fetch it.

“You know, Bokke,” Chooks said after a long pause, “I still dream about those days. Not nightmares – more like… echoes. The smell of gun oil, dust, the sound of FNs clicking off safe. Feels like yesterday.”

Bokke’s face tightened, eyes somewhere far upriver. “You were in for the last four years, hey? Lucky you. I did my first call-up in seventy-four. Mount Darwin. Full-on hondo. Whole country going tits up while the pommies still waxed and whined about oil sanctions.”

“Ja, I came in when it was winding down, or so I thought” Chooks replied. “Got worse. Operation Hurricane days. I was first at Inkomo. We did one stick in the lowveld near Chiredzi. Hot, full of jesse. Couldn’t see a bloody thing past five yards. Then – boom, contact. Three terrs, maybe four. We let off everything. I still hear the echoes.”

Bokke nodded slowly. “We all had our moments, chief. Bush was full of ghosts, even then. Sometimes I think the trees remember more than we do – at least most of them are still standing.”

He poured another measure of Mainstay and Coke, the old stalwart, Spook and Diesel, swirling the glass.

“You know, first time I slotted a gook, I thought I’d feel something. Didn’t. Nothing. Not till later. That’s the trick no one tells you – the feeling waits. Years later, it hits you like a bloody thunderbox lid.”

Chooks looked down. “You still have those dreams?”

“Ag, sometimes. Hear a twig snap and the brain says, contact right! even if it’s just a bloody dassie. The ears remember before the heart forgets.”

They sat quietly for a moment. Banda, sensing the shift, turned down the music.

Only the distant rumble of the Falls – despite the low season – filled the tropical silence.

“Remember the rat packs?” Bokke said, forcing a grin. “Brown beans, jungle juice, and that bloody powdered orange kak. You’d trade your soul for a bottle of Mrs Balls or a cold RGT.”

“Ja nee,” Chooks chuckled. “And those blerrie sitreps every morning, often full of bulldust optimism: NTR, no significant enemy movement reported. Meanwhile, we were knee-deep in kak: tsetse, dongas, gooks and blerrie land mines.”

“Don’t forget those mujibas, hey. Little buggers could hear a pin drop two clicks away. I once had a picannin laaitie warn me about a minefield. Saved my arse, that one. Gave him a tin of OXO cubes. Thought it was Christmas”

Chooks smiled. “Funny how it all blurs now. The bush, the heat, the patrols, sitting round, sweat, smoke. Sometimes I think we fought for ghosts.”

Bokke’s’ laugh was slightly bitter. “We did, my china. For the ghost of an idea. Rhodesia first, then Zimbabwe. Whatever you want to call it now.”

‘Ja, we thought we were the kings of Africa. Turns out we were just caretakers of someone else’s dream.”

“Are you still angry, boet?”

“Angry? No. Just tired. Tired of pretending the war ended. It didn’t. It just changed shape. Now it’s fought with slogans, dodgy banknotes, Lucky Bucks, different houts, and stitched-up elections. Same terrs, different uniforms. Another spiel. Fatter, shinny, and in Armani”

Chooks sighed. “Still, it wasn’t all kak. Remember those Friday nights at the mess? Nyama on the braai, dop, someone strumming John Edmond, and the fwaps trying to preach to the dronk troopies?”

“Ha! Ja, those fwaps with their holy-water bottles. You’d tell them, Padre, pour me a dop instead.”

They both laughed, again, the sound carried by the wind, a release of memory and some regret, with life changed forever, a chunk of youth eaten away, friends lost, too, the past unrecoverable.

Bokke leaned forward, voice low. “You know I still write to Mary, hey? The farmer’s widow from Rusape. Her old man got slotted in seventy-eight. She never left. Runs a boarding house now. Says the land still breathes.”

“That’s brave,” Chooks said softly. “Most couldn’t stay. After eighty, it was gap it, defect to the West, or get pegged.”

“Ja. I stayed far too long. Thought we’d ride it out, ok. Then came the invasions. Woke up one morning to a bakkie full of war vets chanting hondo, hondo! – and waving machetes.

“Banda here was working for me then – you remember that Banda?”

Banda nodded slowly from behind the counter. “Yes, baas Bokke. I remember. I was young. There was shouting, then fire. We ran to the river”

“Yebo,” Bokke said. “Fire everywhere. They burned the fields, barn and the sheds, the house, even the compound. Took all the cattle. I drove off with what I could fit in the Landy. Never went back, probably never could.”

Chooks reached across and touched the rim of Bokke’s glass. “You made it out, boet.”

“Ja,” Bokke muttered. “But half the ouens I served with didn’t. Some pegged it in the bush, others later. One even hung himself in Perth. Another drank himself into a slow puncture in Durban. Not all of us survived. We all went down different ways.”

The frogs grew louder, the sky, darker. The moon rose, pale above the river, now shimmering silver.

Memoire

Chooks broke the silence. “You ever think of writing it down? All this. The good, bad and ugly, the slang, the laughs, the madness.”

“Ha! Who’d read it? The kids today don’t even know what an FN is. They think Chilapalapa’s a band.”

“Maybe that’s why you should write it,” Chooks said. “To remember us before the ghosts fade.”

Booke stared out across the river. “Maybe you could and should, Chooks. You were the one with the words. Me, I just knew how to plant tobacco and shoot straight.”

“Maybe both,” Chooks said with a smile. “You tell it, I’ll write it. Two Rhodies at a bar, ek se.”

They laughed again, softer this time, a shared conspiratorial sound under the hum of Africa at night.

The lanterns flickered as a warm wind swept off the river.

Banda collected the empty glasses, leaving the unfinished whiskey bottle. The tourists were gone now, leaving only the two men and the river’s endless murmur.

“Same time tomorrow?” Chooks asked.

“Depends, if I wake up.”

“Ag, you will. Rhodies never die that easy.”

“Ja, nee,” Bokke said. “We just fade, hey, like old beer labels.”

They clinked glasses one last time under the bright-lit African moon and trundled off into the night.

Exodus

The next evening began the same way: a heat haze over the river, the air thick with dust and frangipani.

Bokke arrived first again, claiming the same table beneath the thatch eaves.

Banda had the beers lined up before he even spoke.

Chooks appeared just a few minutes later, still wearing the same old khaki shirt from the night before, sleeves rolled to the elbows, copper bracelet on the right wrist.

“Evening, chief,” he said. “Same again?”

“Ja, make it two. I’m as dry as a mopane stick.”

They clinked bottles, a ritual now. Behind them, a generator coughed to life somewhere in town. It was blackout time again, thanks to Zesa.

“You remember Independence Day?” Chooks asked quietly. “Eighty. The flags, the fireworks, Bob and the bishop on the stage? Even Bob Marley? And that fat Pom?”

Bokke gave a short laugh. “Ja, and us all watching from the mess, pretending to toast peace while wondering who’d be pegged next. We all knew it wasn’t the end. Just a new day for the same old story.”

Chooks swirled his beer. “I marched that day, you know. They told us it was for unity. I believed them for five minutes.”

“Then came the tough party line, the hit lists, checkpoints, the whispers about Gukurahundi.”

“Those years were then, and are even now, still for me a blur,” Bokke muttered. “Farmers disappearing, friends taking the gap, called it the ‘owl run’, you know, lota army okes heading Down South.”

“I tried to hang on. Thought I’d be one of the main manne who could make it work. I even went to Harare for a landowner license meeting.”

One of those party chefs there told me, ‘Old man, it’s time to share the land.’ I said, ‘Chief, I’ve been sharing it for forty years.’ He didn’t laugh. Had a manic look in his eyes”

They drank again, the river gleaming like hammered bronze.

“You ever think of leaving?” Chooks asked.

“Thought about it plenty. Never did. My boet went to Perth, opened a car shop. Hates the place, and the Aussies, but he’s got electricity.”

“Ja, mine’s in Kent. Can’t handle the Brit weather. Says even the pigeons look miserable.”

They laughed softly.

Rhodies Till We Die

“Funny thing, exile,” Chooks said. “You leave for nowhere and never really arrive anywhere. You just keep on explaining where you came from. No one understands.”

“Ag, man, you know what they call us now? Whenwes. When we had farms, when we had Rhodesia, when we had real beer.”

Chooks smiled. “Maybe we earned that name. Every Rhodie pub in London beats to the sounds of a broken record.”

“Still better than being called a sell-out like with the munts,” Bokke replied. “Here, you’re either loyal or invisible.”

Banda, polishing a glass nearby, grinned. “You two bwana talk too much old history. You should run for Parliament.”

Bokke barked out a laugh. “I did once, Banda. Got only one vote. My own. Even the wife didn’t bother.”

The barman chuckled and retreated to the counter.

Chooks leaned forward. “You know what I miss? The bush and red earth smell after the rain. That first breath of guti in Inyanga. The way the msasa turns red in spring. You can’t buy or export that.”

Bokke nodded slowly. “That’s the curse for us Rhodies. We carry a country in our heads that doesn’t exist anymore.”

The Lost Years

By the time the ritual whiskey bottle arrived, the talk had shifted to money—or what passed for it.

“Remember 2008?” Bokke said. “Ten bllion bucks for a loaf of bread. Banda used to count zeros until the ink ran out.”

Banda laughed from behind the bar. “I keep one note. Just in case. The hundred trillion. In case I run out of mali, and good for starting the braai.”

“Ag, those were kak days,” Chooks said. “I’d get paid in the morning and already by lunch it was worth bugger-all. We used to joke we were trillionaires at breakfast, paupers by tea.”

“Not a joke for long,” Bokke muttered. “I sold the last tractor tyre for diesel. The banks were empty, had no cash, shelves bare. Even the cockroaches emigrated.”

Chooks chuckled. “And still we stayed. Why?”

“Because somewhere under all that kak was home”, Bokke said. “And because we’re stubborn bastards.”

He topped up their whiskey glasses.

“When the Zim dollar died, I started taking payments in beer. The best move ever. Banda would back me up on that.”

“True, baas,” Banda said. “Beer never lost value.”

Politics

“Then came the new dispensation,” Choos said, sarcasm dripping. “Same chefs, shinier suits, new slogans.”

“Ja, Operation Restore Kleptocracy,” Bokke replied.

“Everyone thought it was a fresh start. Only thing fresh was the ink on the new notes, then the ZiG that soon zagged.”

“Still,” Chooks said, “you must admit, there’s less fear now, hey.”

“Less? You try farming again without any bodyguard. The only thing less is diesel in the tank.”

They both sat back, letting the night air cool the sweat on their arms. Somewhere downriver, a lion coughed.

“Remember how we used to sing ‘Rhodesians Never Die’?” Chooks said. “Ja,” Bokke said. “Now we just refuse to live anywhere else.”

Nightfall

The moon rose higher, its pale shadow cast over the Zambezi.

Banda dimmed the lanterns. The bar was nearly empty, only the hum of insects and the hiss of the river could be heard.

“Chooks,” Bokke said quietly, “you ever wonder what it was all for?”

Taking a long sip before answering, “Maybe it was just life, boet. We were born, we fought, we farmed, we loved. That’s enough.”

“Sometimes I think we were just holding a line on a map that no one else could see.”

“Ja. But we held it, hey. For a while.”

They watched a hippo’s back ripple through the Zambezi current. Unseen, unknown, silent, like terrs in the night.

Bokke tapped his glass against the table.

“Thing is ,my china, that river doesn’t care who won what, who lost, or whatever. Same water, same flow. Maybe that’s what peace looks like.”

Chooks smiled. “Then here’s to the river.”

They raised their near-empty glasses, the whiskey inside glowing like fireflies in the moonlit night light.

After a moment, Bokke said, “If I peg tomorrow, scatter me here, near the drift. No speeches. Just cold beers and a laugh.”

“Done,” Chooks said. “But not tomorrow. We’ve still got stories.”

“Yussus, plenty, that’s for sure. Like that time with the crocodile near Binga, remember”

“Save it for the next round.”

They laughed again, softer now, a sound that belonged to men who had seen too much and somehow endured.

Banda turned off the last light.

The bar sank back into the darkness, the river whispering below like memory itself.

The River

Next morning, outside, the chairs were all empty, the glasses dry.

Only Banda sweeping dust from the veranda and the river carrying on its endless business.

He paused, looking toward the riverbank where two old footprints marked the earth. He smiled to himself.

“Same time tonight,” he murmured, and kept on sweeping.

About the Author

Duncan Clarke is a third generation Rhodesian born in Salisbury in 1948, with antecedents there from 1897. The river bar on the Zambezi, in Zimbabwe, exists, and is a private club. Many members are ex-Rhodesians and of a certain vintage.

Discover more from Africa Unauthorised

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I was born in Rhodesia in 1947, the middle child of five. My grandfather was in the pioneer column and in ‘E’ Troop Rhodesia Volunteers. He served in the ill faited Jameson Raid. My wife was schooled at Mary Mount College Umtali. I served ten years in the BSAP, went into small business and was finally forced out. We settled in Australia and prospered. I spent a lifetime feeling awkwareloy aggrieved so after retiredment, I was a businessman and lawyer, I undertook research and a deep dive. If you want to know the definitive truth about what happened to Rhodesia read my book ‘Perfidious Albion’. It is serious reading and available with Amazon.

THANK YOU FAMILY!….an Airline Captain from the rox (MTNS) in Colorado USA!…a CHRISTIAN missionary working several times in ZIM with Castle Rock CO church members to help the 9000 orphans from the SHONA team. We helped re-build FIVE schools and the Hospital plus drill 18 potable water wells and repair, repair and fix…ONLY place/location in my life (sp Namishato) (now I’m 84) that NO MATTER what I did for the Roddie’s it was unquestioned and GOOD!!! FAITH HOPE LOVE capt. dale buss now retired?? to sunny FLA..usa GOD’S GRACE and BLESSINGS ALL…!!

Brilliant. A powerful story told with great poignancy. In two generations they built a country ……with warts and all.

Is this a once off story or a new book by Duncan Clarke ?

In any event – a most enjoyable read.

Hi Rudolf it’s a short story and Duncan is putting them on Kindle.

I love this story, and I’m a Kiwi. Who loves Zimbabwe. While this story rings true, and is full

of the pathos of Rhodesia, it bubbles with the humour that Zimbabweans of all persuasions are full of.

I’ve spent many evenings at this very bar,

In 2025, and loved every minute of it. It’s full of young people and their children too. Who also love Zimbabwe and are making a rich and rewarding life there. Just like the Rhodies. Because as everyone reading this knows, Africa endures.