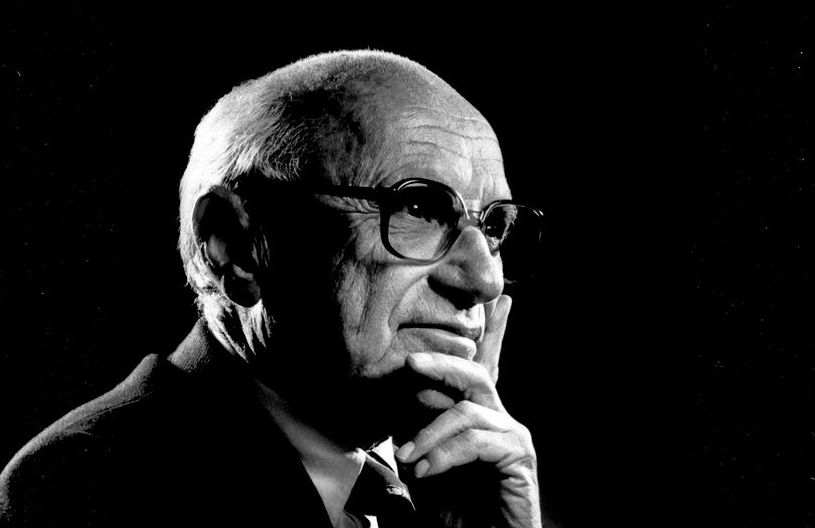

by Milton Friedman

Of the 49 countries in Africa, fifteen are under direct military rule and 29 have one-party civilian governments. Only five have multiparty political systems. I have just returned from visiting two of these five—the Republic of South Africa and Rhodesia (the other three, for Africa buffs, are Botswana, Gambia and Mauritius). If this way of putting it produces a double take, that is its purpose. The actual situation in both South Africa and Rhodesia is very different from and very much more complex than the black-white stereotypes presented by both our government and the press. And the situation in Rhodesia is very different from that in South Africa.

Neither country is an ideal democracy—just as we are not. Both have serious racial problems— just as we have. Both can be justly criticized for not moving faster to eliminate discrimination— just as we can. But both provide a larger measure of freedom and affluence for all their residents—black and white—than most other countries of Africa.

Both would be great prizes for the Soviets—and our official policy appears well designed to assure that the Soviets succeed in following up their victory in Angola through the use of Cuban troops by similar take-overs in Rhodesia and South Africa.

The United Nations recently renewed and strengthened its sanctions against Rhodesia. The U.S. regrettably concurred. We have, however, had enough sense to continue buying chrome from Rhodesia under the Byrd amendment, rather than, as we did for a time, in effect forcing Rhodesia to sell its chrome to Russia (also technically a party to the sanctions) which promptly sold us chrome at double the price.

Rhodesia was opened up to the rest of the world less than a century ago by British pioneers. Since then, Rhodesia has developed rapidly, primarily through its mineral production—gold, copper, chrome and such—and through highly productive agriculture.

In the past two decades alone, the “African” (i.e., black) population has more than doubled, to 6 million, while the “European” population (i.e., white) has less than doubled, from about 180,000 to less than 300,000. As Rhodesia has developed, more and more Africans have been drawn from their traditional barter economy into the modern market sector. For example, from 1958 to 1975, the total earnings of African employees quadrupled, while those of European employees a little more than tripled. Even so, perhaps more than half of all Africans are still living in the traditional subsistence sector.

Europeans have a much higher average income than Africans in the market sector—perhaps in the ratio of as much as 10 to 1. But Africans in the market sector have a much higher average income than their fellows in the traditional sector—in about the same ratio. Both Europeans and Africans have benefited from their cooperation. Modern cities like Salisbury, an extensive network of roads and communications, productive farm lands, mines and industrial works—all this would have been impossible for a population of whites that even today totals fewer than 2-300,000.

On the other hand, without the knowledge, skill and capital provided by the whites, Rhodesian blacks would today be many fewer and far poorer. To judge from the crude evidence that is available, the Rhodesian blacks in the modern sector enjoy an average income that is considerably more than twice as high as that of all the residents of the rest of Africa, excluding only South Africa.

The relation of the whites to the blacks is complex: a large dose of paternalism, social separation, discrimination in land ownership, and little or no official discrimination in other respects. In particular, there is no evidence of that petty apartheid—separate post-office entrances, toilets, and the like—that was our shame in the South and that I find so galling in South Africa. The education of the blacks has been proceeding by leaps and bounds. Today, half or more of the students at the University of Rhodesia are black.

Guerrilla warfare from outside and inside the country has produced a reaction by the government that can properly be described as repressive. But the provocation has clearly been great and it is important to maintain a sense of proportion. More than half the defense forces patrolling the borders are black. We were told that more blacks volunteer for the defense forces than can be accepted.

The streets of Salisbury give a visual impression of a black sea with occasional white faces that brings to life and gives new meaning to the 20-to-1 numerical population ratio. It is very difficult to reconcile that visual impression with any widespread oppression or feelings of oppression by the blacks. If that existed, Rhodesia could not easily maintain such internal harmony or so prosperous an economy.

During the past ten years of sanctions, Rhodesia grew in real terms more rapidly than in the prior ten years—and more rapidly than the rest of Africa. The external pressures against Rhodesia arise from its unwillingness to grant “majority rule” within a definite and brief timetable. Whatever the merits or demerits of “majority rule” as an abstract principle, the imposition of sanctions against Rhodesia on this ground is a striking example of a double standard. The other former African colonies of Britain that were granted independence without question and without sanctions do not have anything approximating what Americans regard as majority rule. They have minority rule by a black elite that controls the one party permitted to exist. If the elite minority in Rhodesia had happened to be black instead of white, Britain would have rushed to grant them independence and provide “development assistance.”

“Majority rule” for Rhodesia today is a euphemism for a black-minority government, which would almost surely mean both the eviction or exodus of most of the whites and also a drastically lower level of living and of opportunity for the masses of black Rhodesians. That, at any event, has been the typical experience in Africa—most recently in Mozambique.

In his trip to Black Africa, Secretary Kissinger would do well to talk to some of the exploited masses and not only the elite—but needless to say, he will not find it easy to do so in the one-party states. Rhodesia has a freer press, a more democratic form of government, a greater sympathy with Western ideals than most if not all of the states of Black Africa. Yet we play straight into the hands of our Communist enemies by imposing sanctions on it! The Minister of Justice of Rhodesia cannot get a visa to visit the U.S.—yet we welcome the ministers of the Gulag Archipelago with open arms. James Burnham had the right phrase for it: Suicide of the West.

“Rhodesia” by Milton Friedman Newsweek, 3 May 1976, p. 77 ©The Newsweek/Daily Beast Company LLC

______________________________________________________________________________ Compiled by Robert Leeson and Charles Palm as part of their “Collected Works of Milton Friedman” project. Reformatted for the Web. 10/26/12

Discover more from Africa Unauthorised

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What I find, that never fails to amaze me, is how ignorant we are to the facts that surround us through our life. How we expect others to be able to see and accept how things are within ‘our’ environment when all the time they are only concerned (mostly), with what is happening within their own, of course.

The majority of this planets inhabitants spend most of their time ‘surviving’, making life work as best they can for themselves and their ‘own’. We place our blind faith in professionals, governments, organisations and world leaders, in the hopes that they would carry out their jobs as we might if we had that responsibility.

We humans can be ‘categorised’, pigeon holed, profiled, because of our behaviour and thinking, no matter how much the new generation would like to believe this to be ‘politically incorrect’. Being politically incorrect has the unfortunate effect of blinding us from the truth on so many occasions (too many), that those who wish to exploit the situation are given too much freedom and assistance with which to do so.

Just like any situation when interaction between humans becomes tense, things are said which are clearly wrong or inaccurate (in hind sight), but, just as with lessor wrong situations we should allow (and encourage), parties to apologise and make good repair to the bad decisions and speeches made where the intent is honourable. We humans fail. It’s how we learn, if we take advantage of the lessons to be learnt. But where we fail mostly, and do not seem to be learning from, are the incorrect actions by the political bullies who railroad their own greedy intentions and plans over a situation that could have been bettered with the patience and guidance, and time.

It is the impatient who demand that ‘God, give me patience, BUT GIVE IT TO ME NOW’, who we allow to break and disturb the slow growing harmony that would help us to learn at the pace required for a stronger future.

Why can’t we see the ’cause and effect’ in the actions of the greedy giants of our world. The results are in plain sight for those who want to see.

What happened with Rhodesia, the country, was wrong. Not everything in it was right, but could have been made right, slowly, with the time and patience (and interference), required for a situation so complex. The situation within Rhodesia before Britain blew the whistle, was in a far better state of harmony than Britain itself.

Well the west now has their winds of change , big trouble coming. A beautiful country destroyed.