by Aidan Hartley

Many of my British tribe fled Kenya around independence in 1963 because they believed there was no future. Gerald Hanley, an Irish novelist who knew the country, forecast ‘a huge slum on the edge of the West, Africans in torn trousers leaning against tin shacks, the whites of their eyes gone yellow, hands miserably in their pockets…’

For sure, poverty here is an awful, destabilising reality. But Kenya’s past 51 years is a story of hard work and enterprise in which there has been real social mobility and countless stories of rags to riches. In everything from finance to farming, Kenyans are Africa’s most successful capitalists. Still, for a middle-class person to come good in 1963, all you needed to do was buy a Nairobi house for a few quid from one of those fleeing colonials and do nothing else except drink a bottle of gin a day, and you’d have made a lot of money.

People have been predicting my home’s imminent demise for 51 years. In 2000 Blaine Harden, a top American correspondent once based here, wrote of the ‘decline of nearly everything in Kenya’, which previously had been ‘a celebrated exception to the rule of misrule in sub-Saharan Africa’. Meanwhile a dynamic, complex economy and society has been building up.

In 25 years I have seen half a dozen generations of foreign correspondents and diplomats come and go. Many arrive full of beans and hope, in chinos. They buy bark-cloth wall hangings, sample maize meal, say liberal things. Some stay for the rest of their lives because they’ve found their place. Others — four years later they’re like Kurtz up the river. The roads, the cops, the stuff they see daily just gets to them. They write about the ‘formerly stable Kenya’. As they jog for the departure gate to new international postings, their parting shots are full of doom.

Then up turns the new replacement in his Banana Republics, holding his inflatable exercise ball. ‘This country is kaput,’ says one diplomat every single time I see him at cocktail parties. ‘How long have we got?’ I probe while lunging for the canapés. Anecdotes follow about the latest outrages as I recharge my glass of merlot. The latest thing is terrorism. Before that it was ethnic violence, crime, corruption. This just goes on and on, year after year. My advice is always: ‘What you must do is buy a house. Do you like gin…?’

It’s not that I’m against foreign hacks or diplomats. I don’t, as many do, vilify them for dishing out the bad news. We need to hear the bad news. And I think it’s wonderful they can all be here puncturing our dreams of a rising Africa, because of course they would not be doing this in Mogadishu or Juba. They live in Nairobi and fly out to those places, whereas here foreign investment quadrupled in a single year last year and the international families are piling in. Even life in supposedly stable countries such as Tanzania — or South Africa — cannot compare with Kenya in what they offer.

Maybe I am a frog in a saucepan of heating water, but I am not without foresight. I thought a lot about life after being ambushed by a bandit who filled my car with bullets last year. I’ve logged all the newspaper reports of terrorism attacks since the end of the Westgate shopping mall massacre in September. My count of reported incidents gives a total of 60 innocents killed in nearly 30 events, some very close to home. I am concerned daily for my family. The roads drive me crazy. And so does bureaucracy and corruption. The poverty I see disturbs me to the core.

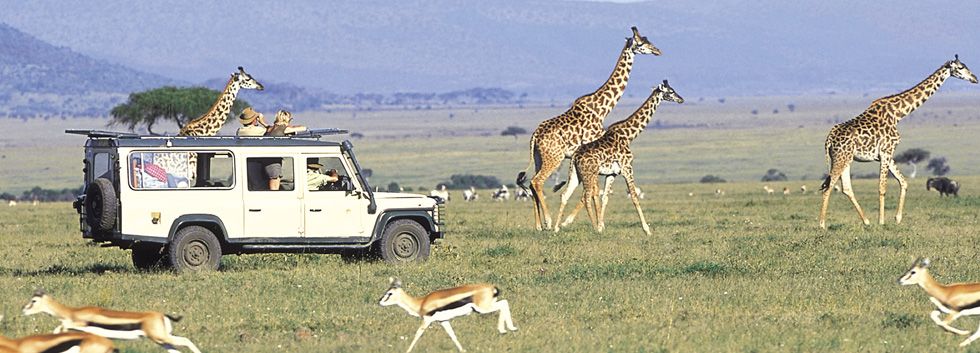

But those of us who have made Kenya our home do not regard it as a ‘formerly stable ally of the West’. We hope to be resilient whatever happens. My mother slept with a revolver under her pillow in the 1950s but my parents never once considered abandoning our home. We see a great future here. We enjoy Kenya: the people, the still wide open spaces, the best safaris, the Tusker beer, the days of toil and nights of joy. Whatever they say about Kenya, Britain remains a great friend — the biggest investor, with the biggest tax-paying companies, the largest expatriate community, the closest connections of history and culture. The British are still the largest group of visitors to Kenya because they see the wonder and magic of the place. I’m concerned that all these good things happening here are being ignored. This in the end will hurt us all. We are not going to be brought down by a few foreign Muslim lunatics out to disrupt life. Please take your holiday in Kenya this year. In case any readers of The Spectator are passing our way this summer, you are very welcome for a beer.

This article first appeared in the print edition of The Spectator magazine, dated 21 June 2014

Discover more from Africa Unauthorised

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.